IV. A Filipino clergy emerges

The friars were not without defects. By the 18th century, the parishes had become too dependent on the missionary orders, stunting the development of native priests. The bishops at first attempted to break the hold of the friars by asserting their visitation rights over the parishes. The friars, of course, resisted another layer of authority and wanted to be answerable solely to their religious superiors. They threatened repeatedly to abandon their parishes and the bishops backed out. The dispute over “secularization,” which initially took on a racial overtone, became a nationalist cause.

According to the Dominican historian Fr. Lucio Gutierrez, the first native Filipino to be ordained to the priesthood was Agustin Tabuyo of Cagayan (1621), followed by Miguel Jeronimo of Pampanga (1653). The Jesuit historian Fr. John Schumacher, however, contends it is doubtful if Tabuyo and Jeronimo were indeed natives. The “first definitely known Indio priest” was Francisco Baluyot, ordained in December 1698, according to Schumacher. Ordinations were few and far between as the Jesuit and Dominican colleges produced few candidates, and these were Philippine-born Spaniards. Moreover, the policy in Spanish America of not ordaining natives was carried over to the East Indies. By 1768, the Archbishop of Manila, Basilio Sancho y Santas Justa y Rufina, was confident enough to insist on the visitation and secularization of the parishes. In 1773, he built the Seminary of San Carlos on the site of the University of San Ignacio, which had been abandoned due to the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1768. Sancho proceeded posthaste to train and ordain secular priests, as he needed them to take over the parishes and at the same time replace the expelled Jesuits.

The wave of secularization failed. It bred enmity; for one, the takeover from the Augustinians in Pampanga, led by Governor-General Simon de Anda himself, turned violent. Secular priests proved to be ill-prepared and poorly trained to take over the parishes. In 1787 the colonial government petitioned the king to put an end to secularization. It continued, however, with the number of missionaries sent to the islands by the friar orders dwindling as a result of the imposition of diocesan visitation. It did not help that the friars became denouncers of Spanish officials, causing the latter’s resentment. Government intervention in clerical posts also intensified, with Spain stretching the limits of the Patronato Real, the age-old papal concession of religious affairs to the king in exchange for material support to the missionary campaign. Religious fervor of the friars waned. Worse, discipline was relaxed.

Many in the secular clergy eventually proved worthy of their vocation, and began to fight for their rights to take back the parishes. The cause was led by Fr. Pedro Pelaez, an outstanding priest and academic who raised funds to send a representative to Madrid, wrote pamphlets in favor of secularization, and petitioned the Queen of Spain for support. He was succeeded by his protege Fr. Jose Burgos, the most brilliant student ever to come out of the portals of the University of Santo Tomas. Another secular, Fr. Mariano Gomez, did not possess the same credentials, but was nonetheless an excellent organizer.

Fr. Pedro Pelaez, leader of the secularization movement (Kasaysayan book)

Fr. Jose Burgos (right) and Frs. Jacinto Zamora and Mariano Gomez, executed in 1872

The return of the Jesuits in 1859, nearly a century after their expulsion over political controversy in Europe, exacerbated the situation. The Jesuits got back their Mindanao parishes from the Recollects, who had to be reassigned elsewhere. The Filipino clergy felt deprived. In Cavite, secular priests were evicted in favor of the Recollects and Dominicans. Pelaez, vicar capitular of the Manila archdiocese, was himself overruled when he appointed a secular to Antipolo. The post went to a Spanish Recollect. The Spanish government had become suspicious of native clergy given the experiences of Mexico and Peru whose revolutions were led by secular priests.

At age 28, Padre Burgos rose to the rectorship of Manila Cathedral and captured public attention when he countered a series of newspaper articles by a Franciscan belittling the secular clergy. Prior to that, an anonymous manifiesto extolling the virtues of Filipino priests, widely attributed to Burgos, circulated in Manila. The story of Burgos ended in the garrote vil. He, along with Fathers Gomez and Jacinto Zamora, was implicated in the Cavite mutiny of 1872. As there was no evidence except hearsay, the “Gomburza” priests remained in good standing, and the archbishop refused to have them defrocked. The bells tolled for the priestly triumvirate.

Enmities worsened when the Spanish curate of Tondo, Fr. Mariano Gil, uncovered the revolutionary plans of the secret movement Katipunan in 1896. The execution of the nationalist Jose Rizal further heightened the fervor of the revolutionaries. Before his death, Rizal went back to the faith with the help of the Jesuits.

Manila Cathedral and Plaza Mayor, 1852 (Pacto de Sangre)

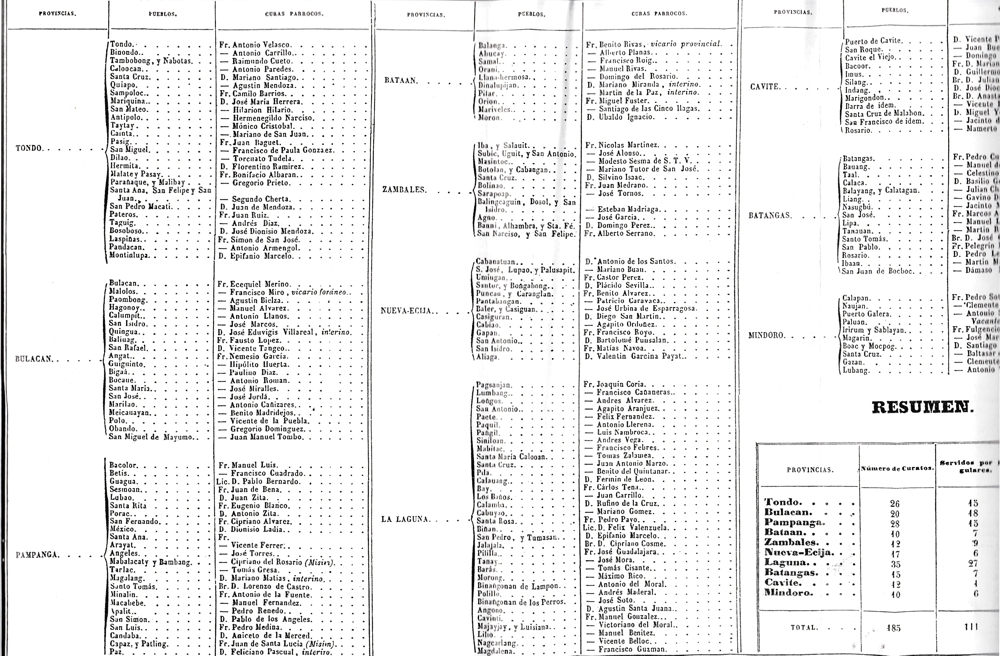

Ecclesiastical status of the Archdiocese of Manila, 1818

At the height of the Philippine Revolution in 1898, there were 967 parishes and missions, more than 800 of which were under the religious orders. The revolution took a heavy toll on the friars. Around 400 of them were captured and many were killed. Among the captives was Jose Hevia Campomanes, Dominican bishop of Nueva Segovia, who tried to escape via Aparri along with 70 Augustinians, three Dominican priests, and eight Dominican sisters.

The arrival of the Americans marked the end of the Patronato Real and for the first time, the Vatican’s direct intervention in the affairs of the Philippine Church. American bishops and the Holy See’s apostolic delegates supported the Filipino clergy. In 1905, the highly qualified Bikolano cleric Jorge Barlin was appointed bishop of Caceres, becoming the first Filipino to rise to the episcopate. Barlin proved very capable and loyal, dealing a blow to the schismatic Iglesia Filipinia Independiente by resisting its recruitment efforts and winning a court battle over church property. Pope Leo XIII himself called for a greater role for Filipino priests in the Apostolic Constitution Quae mari Sinico in 1902. The Pontiff carved out new dioceses and urged bishops to open seminaries to train more young Filipinos for the priesthood. “As experience has clearly shown that in every part of the world a native clergy is of great utility, let the Bishops procure with all diligence that the number of native priests be increased…”

Bishops of the Philippines in 1937